Panel Explores Challenges, Connections, and Paths Forward for Disability Justice, Abolition, and Racial Justice Movements

As awareness of systemic ableism and racism increased, particularly since the onset of the COVID pandemic, so too have responses from policymakers. Yet many of these resulting measures have been controversial and are facing direct challenges from advocates.

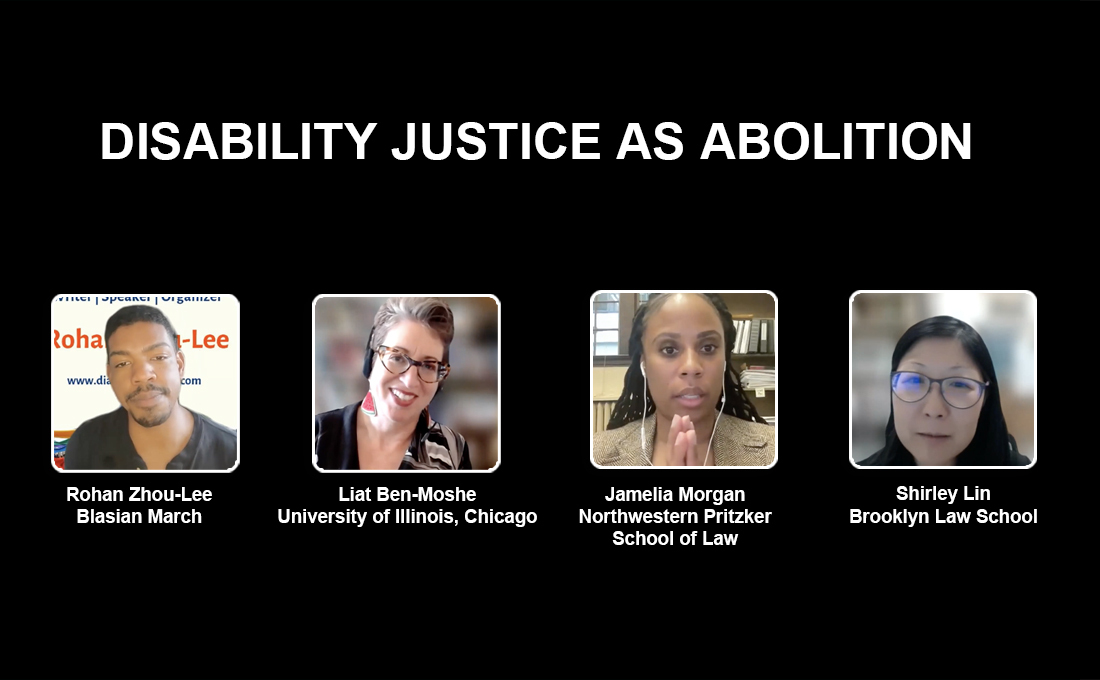

On April 3, the panel discussion “Disability Justice as Abolition” explored the existence of intersectional—and compartmentalized—work among disability justice, abolition, and racial justice movements; the historical narratives surrounding the role of government in addressing human needs; and how to best ensure safety and security for all. Moderated by Brooklyn Law Professor Shirley Lin, the panel was part of the Law School’s Work Law as Privatized Public Law Series.

The distinguished panel included Professor Liat Ben-Moshe, director of graduate studies in criminology, law and justice at the University of Illinois Chicago and author of Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition; Jamelia Morgan, professor of law and director of the Center for Racial and Disability Justice at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law; and Rohan Zhou-Lee, founder and executive director of Blasian March, a Black-Asian-Blasian grassroots solidarity organization.

Lin opened the dialogue by asking panelists to share their work and views on the greatest challenges that have sprung from current policy trends.

Involuntary Institutionalization and Treatment

Morgan and Ben-Moshe spoke of the move toward involuntary treatment of people with mental health disabilities, the involuntary removal of the unhoused, and the present retrenchment efforts against deinstitutionalization, despite strides made since the 1960s.

“We’re again seeing efforts to bring in criminal law to respond to those sets of social issues and the conditions of human existence, such as ‘quality of life’ policing to remove anyone that’s labeled as disorderly,” Morgan noted. “We also are now seeing the changing of standards around civil commitment laws to permit a work-around from the hard-fought victories to have important legal standards that ensure that an individual isn't deprived of their liberty.”

Intersectionality, Morgan added is “essential to doing the work of disentangling punitive and carceral systems that are specifically designed to respond to individuals that society has labeled as non-normative.”

Ben-Moshe cited examples of emerging involuntary treatment programs such as New York’s court-ordered Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), and California’s Proposition 1 and CARE (Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment) Court for those with certain mental health and substance-use issues. She noted the racial aspects of these policies, where, she said, in New York, 44 percent of those subjected to AOT are Black and 32 percent are Hispanic. “It is the practice and belief that people with disabilities need special or extra protections in ways that almost always expand and legitimate further marginalization and further incarceration,” Ben-Moshe said.

We are reneging on the movement toward desegregation and decarceration of those with disabilities or who are housing insecure, she added, a process in the U.S. that focused on “the transition of people with psychiatric or intellectual disabilities from state institutions or hospitals, including psychiatric hospitals, into receiving care in the community.”

The Effects of Racism on Policy

The panelists also discussed the racial elements of the policies.

“Anti-Black racism is composed of pathologization of how people are constructed as dangerous. And that leads to processes of criminalization and processes of medicalization, including psychiatry,” said Ben-Moshe.

Zhou-Lee spoke of the sharp rise in incidences of anti-Asian violence during the pandemic, its continuance, and the pronounced levels of poverty within Asian American communities comparable to that of Black and brown communities. “But society is putting us in silos and making us organize in silos, and that creates bubbles of racism,” Zhou-Lee said. They lauded the transformative justice concept of pod mapping—developed by Mia Mingus, the renowned disabled Asian American Caribbean advocate and theorist. It is a safety structure, developed by disabled communities, consisting of networks of individuals whom one can call on for support.

Zhou-Lee also noted how government responses that invest primarily in punitive infrastructure further harm communities of color, particularly Black and brown communities.

Toward Intersectional Modes of Advocacy

Lin asked panelists to consider what practices would encourage communities to “think outside of what our economic and political system has indoctrinated us to think about, in terms of ‘racial self-interest’ and what ‘rights’ and ‘justice’ look like?”

Ben-Moshe championed the intersectional framework of grassroots disability justice campaigns such as those that fought hard (but have initially lost) against Proposition 1.

Through their work in the Blasian March, Zhou-Lee said, “we try to uplift the stories, integrate these concepts into our work and acknowledge that intersectional history is critical. We always think about the civil rights era that was built on cross-racial disability justice and formed coalitions.”

At the Center for Racial and Disability Justice, Morgan said, “we’re creating a space for knowledge, mobilization, and translation so that communities can engage with the research and can engage with the law, but also work collectively to develop their own solutions through democratic governance and accountability structures and create their own worlds.”

For attorneys and legal workers broadly, Morgan emphasized that there is much work to be done. “I think naming the problem takes work within our field, to create conditions for positive social projects to flourish in line with disability justice,” Morgan said.

The event was sponsored by the Brooklyn Law School Center for Criminal Justice and Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Center for Racial and Disability Justice.